The plague which devours Oran is less a proxy for a manifestly odious occupying force than it is emblematic of the contradictions inherent in democracy, in which the limits of liberal universalism and equality collide against the violent reality of state power. It is telling that Camus chose to set the novel, not in a totalitarian state, but in the liberal-democratic yet still deeply unequal and segregated environment of French Colonial Algeria. While Camus’s experiences during the occupation and as a member of the Resistance undoubtedly influenced The Plague, to construe its narrative as a simple allegory would unjustly limit the breadth and depth of its social critique.

It has often been interpreted as a symbolic rendering of the German occupation of France and the gaping wounds left in French society.

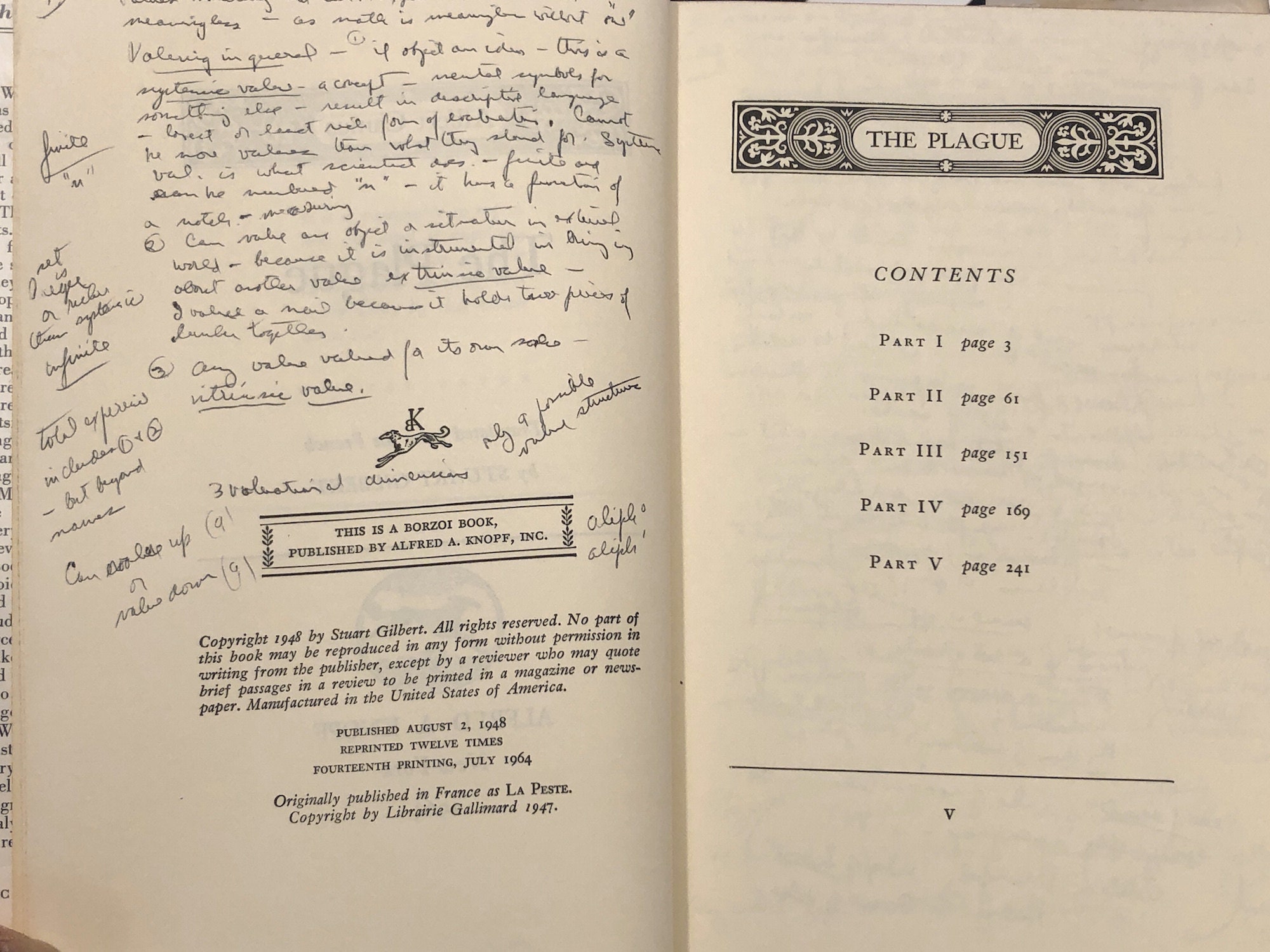

But The Plague is, at its core, a fierce condemnation of authority as domination, with an understanding that as long as it exists, we are susceptible to pestilences-both those that incubate in the human body and those that fester in the human heart.įirst published in 1947, Camus’s novel is the fictional chronicle of a plague that strikes the French Algerian city of Oran sometime in the 1940s. Recent commentators have chosen, understandably, to emphasize aspects with obvious parallels to our present reality.

Interest in the book has renewed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but its seditious quality has generally passed unnoticed. The existence of political authority must, ultimately, lead to murder: That is the message at the heart of Albert Camus’s novel, La Peste, or, as it is known in English, The Plague.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)